RAIMUNDO FIGUEROA:

Instructions for Daily Life

-

This interview was conducted by artist and critic Pedro Vélez for the exhibition “RAIMUNDO FIGUEROA: Instructions for Daily Life” in One Gallery, Bulgaria.

Enduring optimism in Raimundo Figueroa's Instructions for Daily Life.

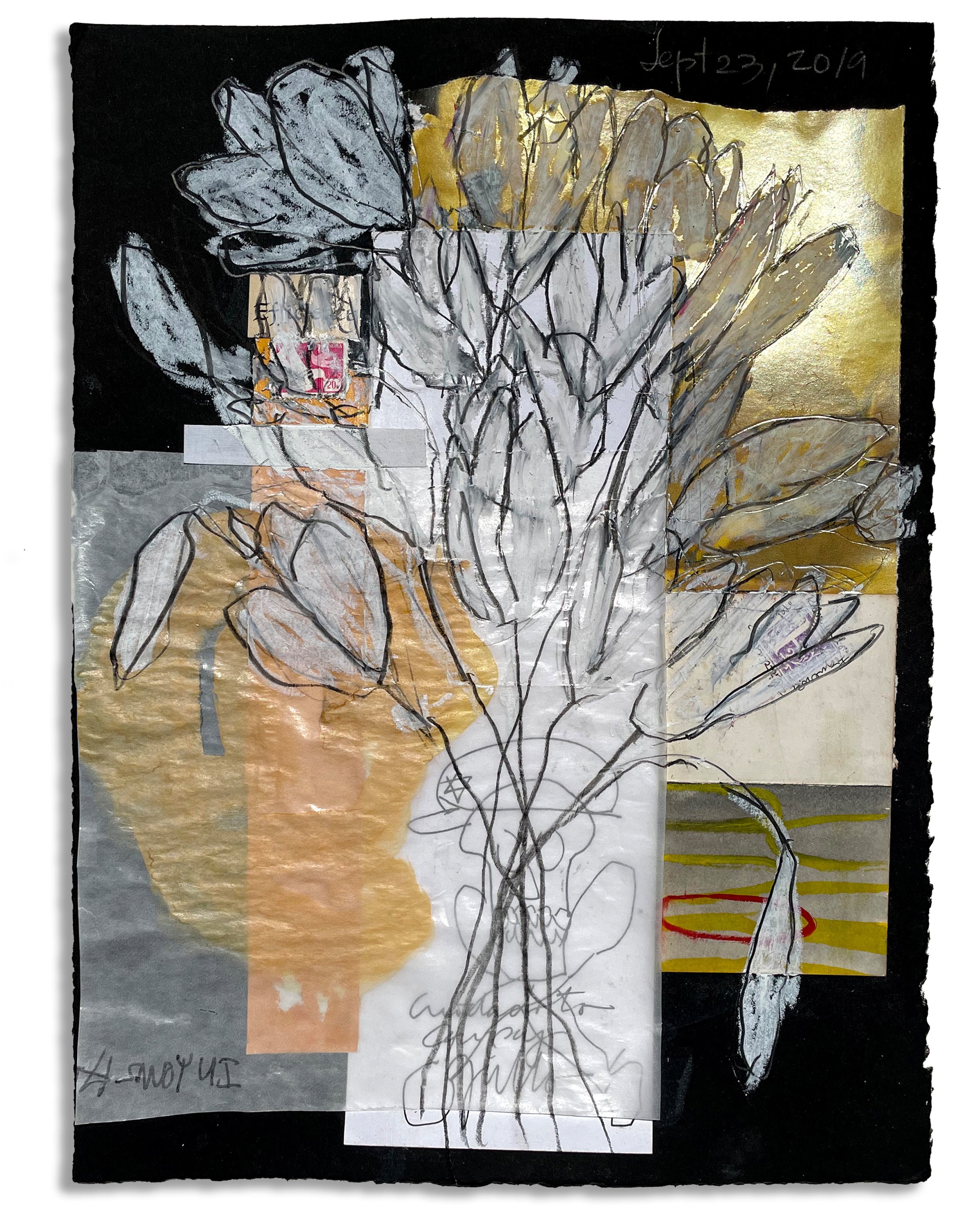

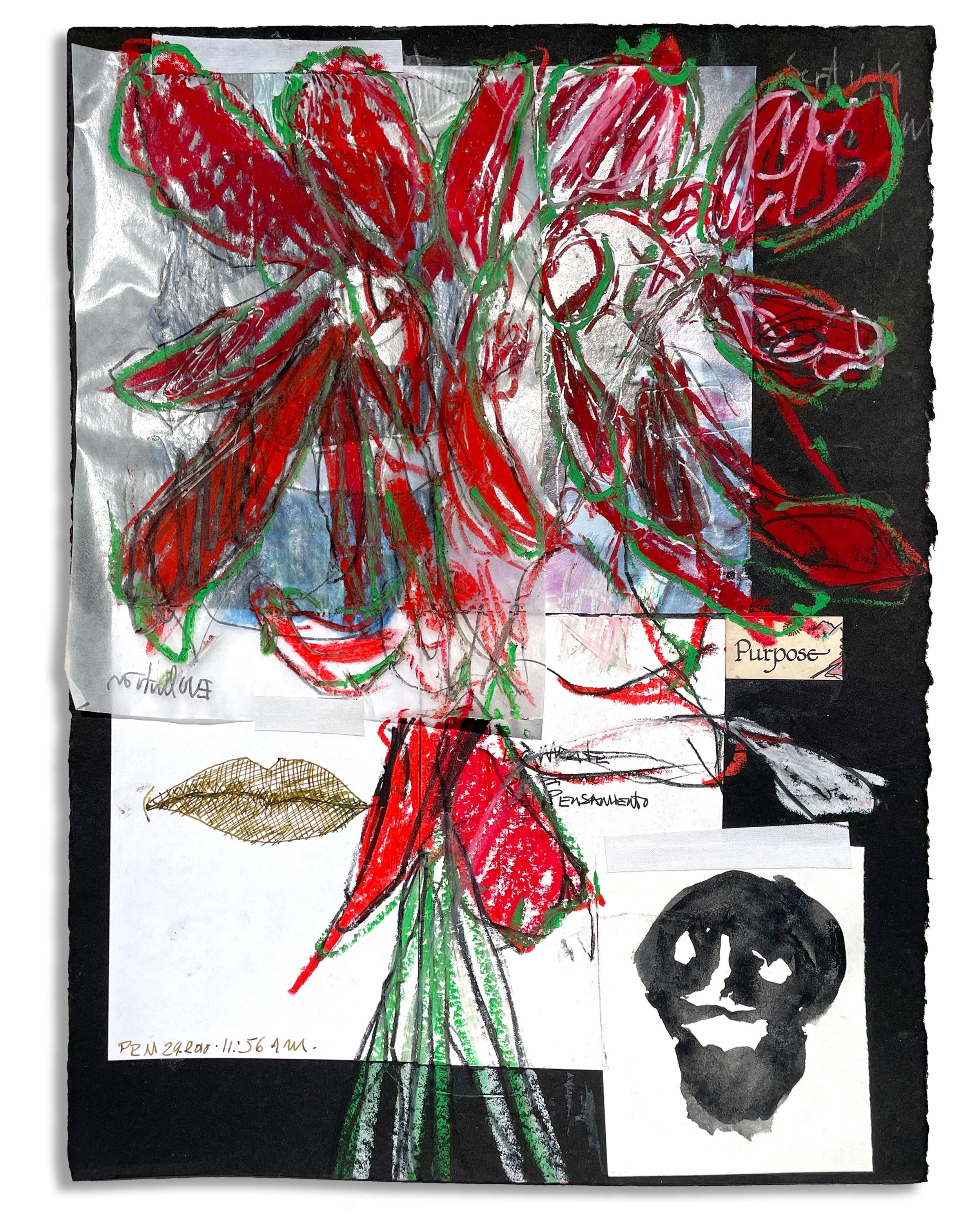

In “Instructions for Daily Life,” a new series of works by Raimundo Figueroa, optimism is employed as a tool for empowerment. The collection features eleven collages and two paintings centered around a bouquet of flowers and presented to the viewer as gifts or offerings of enduring optimism amidst life's everyday hardships. The oil pastel flower bouquets occupy the whole top surface. Underneath, the artist builds his collages in intimate, layered compositions graciously assembled with materials ranging from watercolors, ink drawings, and found objects, including antique postage stamps from places like Argentina as well as Archie comics from the 1960s. The handwritten words and phrases scrawled on top of the surfaces resound like notes of self-empowerment as if the artist is looking at his reflection in the mirror while reciting rhythmically “Be successful; it is an order” or “Be creative all day, always." Figueroa, a violin player and student of music, understands how to use rhythm effectively in composition to lure the viewer into his world of optimistic affirmations for the soul.

Pedro Vélez: How has your training in violin informed your work?

Raimundo Figueroa: Mastering the violin requires a lot of effort and dedication. If two talented young students begin studying simultaneously, one learning to play the piano and the other to play the violin, after two years, the piano student would be playing melodies, while the violin student would still be learning finger placements and how to use the bow. I started playing the violin as a child and played for a long time, perhaps thirty years or more, while studying art history and making art. I learned the discipline of studying in an organized way, practiced scales and arpeggios every day, as well as gained awareness of sound quality and how the sound travels from one's hands to the space. Music is an ephemeral art; once you listen to it, the sound has already passed and only the memory of it remains. I was fortunate to have important composers as my teachers who taught me the importance of studying form and analysis, a key formation for any trained musician. This discipline also became part of my artistic process. When one looks at a well-balanced score, such as Mahler’s Symphony No. 1 or Stravinsky’s The Story of the Soldier, one can see a balanced aesthetic composition like a drawing by Brice Marden or Cy Twombly.

As a violinist, I am an interpreter. When playing a piece from a renowned composer, one becomes a curator of the period. Immersed in the history, social manners, and events of the era and how these influenced the composer and the composition. In contrast, as an artist working with paintings, sculptures, and collages, I am the composer. The one that determines the form, shapes, and resonances of my compositions. My paintings reflect years of introspection, and music is part of my personal development.

PV: You are an avid tennis player. Do you see the discipline of practicing a sport similar to working in the studio?

RF: Sure! Playing tennis and making art are quite alike in terms of discipline and creativity. On the tennis court is where the player’s creativity reigns with different types of shots—like slice, spin, drop shot, and lobs. It’s like how an artist plays with colors and shapes in their studio. But to be good at both, you need to practice a lot. Tennis players train hard before a match, and artists spend time drawing and planning before creating their masterpieces. Once all technical aspects are dominated, it all becomes a mental game. That is the challenging part!

PV: Your work circumvents abstraction and mysticism, and I have noticed the gesture has been a constant throughout the years. Drawing seems integral to your practice.

RF: Throughout my career, I have been drawing and training to become a “virtuoso” of the line. A gestural line with a style that could be identified as mine and only mine.

When I was 10 years old, my mother, who was a university student, used to take me with her on Saturdays to the library and give me lots of art books by masters such as Botticelli, Mantegna, Leonardo Da Vinci, Matisse, Picasso, and Dalí, among others. I used to spend my mornings replicating the pictures in the books. I would use watercolor and ink so that I could draw like the masters. Drawing became a daily habit. Later on, when I lived in Washington, D.C., during the late 1980s, I met Dr. Thomas Lawton, the director of the Freer-Sackler Gallery of Art at the Smithsonian. He was very kind and invited me to visit the archives of Chinese art, specifically concentrating on the early drawings created using Sumi ink. This increased my desire to work with traditional methods. During that time, the masters of philosophy Confucius and Lao Tzu also influenced my work.

PV: Your paintings are also minimal and gestural, like Brice Marden.

RF: When I was developing as an artist during the 70s, Puerto Rico’s Institute of Culture favored figurative art due to the influence Mexico’s Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes had on the Island. At the time, like the Puerto Rican fellow artists that came before me, Rafael Ferrer and Julio Rosado del Valle, I was struggling to break free from figuration and find my own voice and place in the art world. When I moved to New York, I started experimenting with the language of abstraction and found inspiration in the Oriental philosophy of minimalism, as Brice Marden and Ellsworth Kelly did also.

PV: What's the meaning behind the flowers?

RF: This is not the first time I have used the flower as a symbol. In 2013, I did a series called "MIA,” in which the flowers represented emotions related to the war in Iraq. Each painting had a poem on it, but most people focused on the flowers. They thought of them as very beautiful, but the flowers were carrying the weight of the lives that were lost. I wanted them to have that duality. In a sense, all of my work carries a duality.

PV: I have noticed references to Cy Twombly in your recent work. Which other artists have influenced your practice?

RF: I have an immense admiration for Twombly's work. When I look at his painting “Leda and the Swan”, or “Untitled” (Bolsena), to mention a couple, I understand how a work of art can be an object that cannot be avoided. I struggle and aim to be me and only me when I work on my paintings. But, as you can imagine, my subconscious is a huge library filled with images and knowledge of art history, artists, and works. Sometimes these references could come out automatically; what can I do? Kill the memory and move on? The biggest influence in my work comes from artists of the Renaissance like Andrea del Vercocchio, Mantegna, and Botticelli. I am driven by the use of color, forms, and shapes and focused every time on achieving the highest level of virtuosity while executing my paintings. No artist dictated the use of space like Andrea Mantegna.

PV: The art world revels in doom and tragedy, while your recent collages carry optimism. Do you see your positivism as a political stance?

RF: During the past decade, and now more than ever before, we have been bombarded by the news media with fear and misinformation. This has fueled polarization and mistrust of the government and of each other over topics like the pandemic, inflation, race, sexuality, and wars among other things, thus creating a serious problem for humanity.

We attend school when we are young and spend twelve fundamental years in a classroom before going to college, then an additional four years to complete a bachelor's degree, and so on. In most situations, our education doesn't include learning about our inner emotions. We can be highly educated in a specific field but lack knowledge about the mind. Each of us has the power to transform ourselves by understanding and analyzing our own emotions. I believe that this self-knowledge is as sacred and important as any political stance.

PV: What is your concept of beauty?

RF: I have discussed this subject in depth in my collages of the 1990s. For most, beauty is social mannerism, a dogma, an imposed taste. But for me, the sense of goodness that comes when the mind and heart are in communion with something lovely is what beauty is all about. Using this concept, I make paintings. Other fellow artists who came before me also understood such concept and followed that path: Mark Rothko, Ron Gorchov, Brice Marden, and Robert Ryman.

HARMONY 2022 15 x 11 inches Oil pastels, graphite, watercolor, gold leaf, wax paper, and collage elements on paper.

HERMES 2022 15 x 11 inches Oil pastels, graphite, watercolor, wax paper, and collage elements on paper.

NOTHING RESTS, EVERYTHING MOVES, EVERYTHING VIBRATES 2022 15 x 11 inches Oil pastels, graphite, watercolor, wax paper, and collage elements on paper.

BE SUCCESSFUL, IT'S AN ORDER 2022 15 x 11 inches Oil pastels, graphite, watercolor, gold leaf, wax paper, and collage elements on paper.

MAKE IDEAS 2022 15 x 11 inches Oil pastels, graphite, watercolor, wax paper, and collage elements on paper.

CELEBRATE THE DAY AS IF IT WHERE YOUR BIRTHDAY 2022 15 x 11 inches Oil pastels, graphite, watercolor, wax paper, and collage elements on paper.

THE ALL IS INFINITY 2022 15 x 11 inches Oil pastels, graphite, watercolor, wax paper, and collage elements on paper.

LIVE WITH PURPOSE 2022 15 x 11 inches Oil pastels, graphite, watercolor, wax paper, and collage elements on paper.

THOUGHTS ARE FIRE 2022 15 x 11 inches Oil pastels, graphite, watercolor, wax paper, and collage elements on paper.

BE CREATIVE, ALL DAY, ALWAYS 2022 15 x 11 inches Oil pastels, graphite, watercolor, wax paper, and collage elements on paper.

IT'S JUST WHAT I MADE OF IT 2022 15 x 11 inches Graphite, watercolor, and collage elements on paper.